Dr Gautam Wali is an early career research scientist specialising in neuroscience and stem cell research. His research is focused on using Parkinson’s disease patient stem cell models to better understand how the disease works and identify potential drug treatments. Dr Wali is the recipient of the NeuRA Rising Star Award 2023. Funded by a philanthropic foundation, the award provides a three-year program of support to enable one of our smartest and brightest investigators to take their research to the next level. Dr Wali will use this support to develop a personalised drug treatment strategy for people with Parkinson’s disease.

We sit down with Dr Wali to gain an insight into his approach, motivations and the potential impact of his research that sits at the intersection of science and real-world application.

Tell us about your journey into medical research.

I love to learn. From a very early age I had a curious mind. I wondered how things around me worked; how the body works and how the brain controls movement. My interest in neuroscience was fuelled by casual dining table conversations with my father, who is a neurologist, around how complex the brain is and how we still do not completely understand how it works. This is evident by the limited number of cures available for brain diseases compared to other diseases.

Pursuing this interest, I chose to get formal training in cellular and molecular biology through a master’s degree program at the University of Sussex, UK before pursuing my PhD with the late Professor Alan-Mackay Sim, 2017 Australian of the year, at Griffith University. My PhD was focused on using stem cells from the nose to understand the disease-mechanism of neurodegenerative diseases leading to drug discovery. After this, I joined Professor Carolyn Sue’s research lab. Professor Sue is a world leader in Parkinson’s disease research and has led multiple clinical trials. Working with her has helped me get a better insight into the processes and challenges involved in taking research findings from bench to bedside and grow as a translational neuroscientist.

What makes Parkinson’s Disease particularly complex from a research standpoint?

The progressive motor features of Parkinson’s disease (i.e., tremor, bradykinesia, rigidity, and postural instability) are due to the ongoing loss of certain brain cells. About 10 – 15 per cent of Parkinson’s disease patients are associated with genetic mutations, but the remaining 85 – 90 per cent are known as idiopathic i.e., the cause is unknown. No current treatment halts or delays the loss of brain cells mainly because there is a lack of understanding about how or why degeneration occurs.

What progress have you made to find more effective treatments for Parkinson’s disease patients?

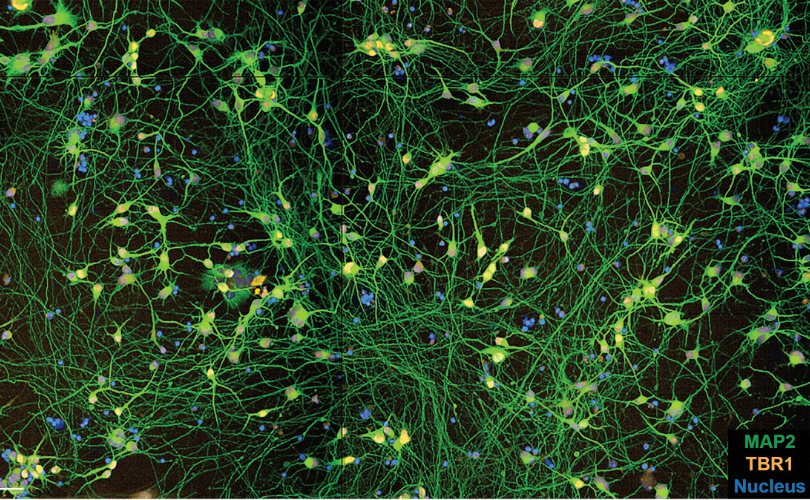

We are working towards an innovative personalised drug treatment approach which involves two key steps. Firstly, growing the patient’s own brain cells in a dish in the lab to understand what cellular processes are altered in their cells, and secondly, testing a range of drug treatment options on these cells to identify the ones that can improve or rescue the altered cells. To achieve this, we have developed a novel machine learning based technology called “Single cell morphomics” that helps us test multiple cellular processes at unprecedented speed and efficiency.

We are confident in this approach because we have already used it to identify a potential drug treatment candidate for SPAST Hereditary spastic paraplegia, another neurodegenerative disease. We are now headed towards the world’s first clinical trial to test a therapeutic treatment for this disease.

How long before you think personalised medicine becomes a reality for patients?

Supported by the NeuRA Rising Star Award, I will be actively focusing on developing this personalised medicine strategy over the next three years. If successful, the drugs identified using this approach will be tested in clinical trials.

What does it mean to you to be a recipient of this Award?

I’m very grateful to the philanthropic foundation for their recognition of my research. Parkinson’s disease was first described about 200 years ago by James Parkinson in 1817 and to date we do not have a drug treatment that can halt/reverse Parkinson’s disease progression. Based on our experience in other neurodegenerative diseases, we believe that the recent developments in stem cell technology and machine-learning can be used to understand the cellular defects and identify a potential drug treatment for each patient individually. This is however a hypothesis at this point. If successful, this will expedite and personalise the drug treatment strategy for Parkinson’s disease patients. I am grateful for this opportunity to advance my research.

Does personalised medicine pose challenges for being able to scale up research?

We’re hoping to make personalised medicine more feasible on a large scale. Our research into other neurodegenerative diseases has shown that some cellular processes altered in the brain cells of people with neurodegeneration are also altered in other cell types (although relatively mild). We are presently investigating if easily accessible samples like blood or skin cells from patients can indicate the defects occurring in the patient’s brain cells. If yes, it may be possible to use, for example, the patient’s blood sample for our personalised drug treatment approach.

As a “rising star” in the field, what advice do you have for young researchers interested in pursuing a career in medical research?

I believe that if you want to do science, you have to be really passionate about it. You should have one of those minds that asks “Why is that?” instead of just accepting the information. It has to be inside you.

Collaboration is often crucial in advancing scientific knowledge. How do you see interdisciplinary collaboration playing a role in addressing the complex challenges of research?

We constantly collaborate with researchers within and outside our field. For example, to develop our novel ”Single cell morphomics” platform, we worked together with artificial intelligence research scientists at Macquarie University, neuroscientists at the University of Sydney and clinicians who have translational expertise to enable rapid translation of our research into health benefits for patients.

For our Parkinson’s disease research program, we are keen to test if the disease-associated effects observed in Australian patients is also present in other populations. We are now collaborating with a university in India to include Indian Parkinson’s disease patients to our research program. This sort of collaboration improves our research as it helps us understand whether our findings are applicable to other populations and importantly, enables us to test scalability.

Above: This image captures human brain cells being grown in a dish in the lab using stem cell technology. It is hoped that studying these cells will unlock how Parkinson’s disease develops and enable the testing of improved drug treatments. The nucleus (blue) is the centre of the cell and the long green are processes known as neurites.